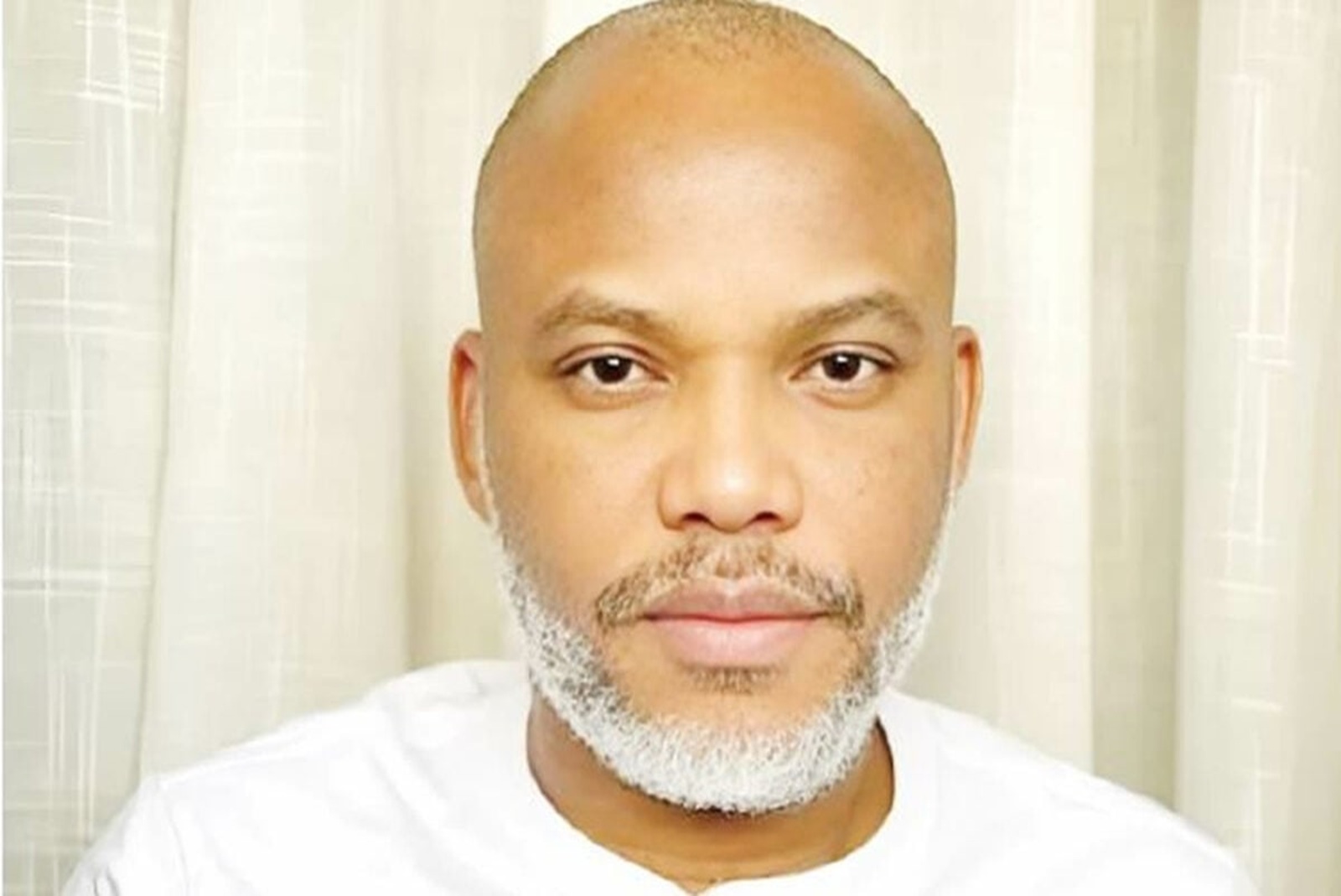

Ibrahim v. Obaje [2019] 3 NWLR (Pt. 1660) 389 at 412, paras. B-D, per Ogunbiyi, JSC:

“I agree with the Respondent’s Counsel that it is not the intendment of the Legislature that Section 22 of the Land Use Act, on consent would limit and deny parties of their rights to use and enjoy land and the fruits thereto in a non-contentious transaction or alienation. The Section cannot be given a literal interpretation as would be seen from the Preamble… The Preambles to the Land Use Act, if looked at carefully and relating it to the case at hand, would reveal that the provision for consent of the Governor must not be applied to transfer of title or alienation of rights between private individuals where there is no overriding public interest or conflict between the parties.”

Notes:

The issue of obtaining Governor’s consent to land transactions in Nigeria has been the subject of many cases before the courts. In fact, Nigerian Real Property Law is replete with case law on the point. The requirement of Governor’s consent is statutorily provided for under Section 22(1) of the Land Use Act: “It shall be unlawful for a holder of a right of Occupancy to alienate same or any part thereof by assignment, mortgage, transfer of possession, sublease or otherwise without the consent of the Governor first had and obtained.” Section 26 further provides that, “Any transaction or any instrument which purports to confer on or rest in any person any interest or right over land other than in accordance with the provisions of this Act shall be null and void.”

In view of the above provisions, it became a trend at some point where a person would sell his land, transferring title to another, but would turn around to attempt to void the transaction on the ground that Governor’s consent was not obtained. In some pathetic cases, such persons succeeded but the Supreme Court has since moved to stop such trending mischief especially when it is clear that the person who has the primary duty to obtain consent is actually the seller. Although, in practice, it is the buyer that ensures that consent is obtained so as to effectively secure his or her interest.

One controversy associated with the consent provisions of the Land Use Act was the issue of whether the land transaction was absolutely void in the absence of Governor’s consent, and whether consent must be “first had and obtained” before the transaction can be said to have been effectively concluded. While the waves of uncertainty trailed, the Supreme Court in the famous case of Awojugbagbe Light Ind. Ltd. v. Chinukwe [1995] 4 NWLR (Pt. 390) 379 rose to the occasion and clarified the point, holding that parties are at liberty to hold negotiations over land transactions and even validly execute relevant documents of transfer such as deeds, prior to obtaining Governor’s consent. The Court reasoned that: “The holder of a statutory right of occupancy is certainly not prohibited by Section 22 (1) of the Land Use Act, 1978, from entering into some form of negotiations which may end with a written agreement for presentation to the Governor for his necessary consent or approval. This is because the Act does not prohibit a written agreement to transfer or alienate land. Thus to hold that a contravention or non-compliance with Section 22 of the Act occurs at the time when the holder of a statutory right of occupancy executes or seals the deed of mortgage will be contrary to the spirit and intendment of Section 22 of the Act.” The apex Court concluded that the legal consequence was that such transaction without consent was inchoate (not void) till consent was obtained.

While the above position brought some comfort to conveyancers, there was yet another disruption when the Supreme Court, per Onnoghen, JSC (as he then was), in C.C.C.T.C.S. Ltd. & Ors. v. Ekpo [2008] 6 NWLR (Pt.1083) 362 held that any transaction without Governor’s consent was not merely inchoate but void. Hear his Lordship: “Though there is no time limit to the obtaining of the said consent by the provision it is very clear that before the alienation can be valid or be said to confer the desired right on the party intended to benefit therefrom, the consent of the Governor of the state concerned must be “first had and obtained.” That does not, by any means, make the transaction without the requisite consent inchoate. It makes it invalid until consent is obtained.” This clearly deviated from Awojugbagbe Light Ind. Ltd. v. Chinukwe. No doubt, the peculiar facts of Ekpo’s case (as briefly highlighted below) influenced the strict position taken by the Court in that case.

Now, the instant case of Ibrahim v. Obaje has brought some freshness into the concept as seen in the statement of the law by Ogunbiyi, JSC where her Ladyship held that “The provision for consent of the Governor must not be applied to transfer of title or alienation of rights between private individuals where there is no overriding public interest or conflict between the parties.” The Jurist heavily relied on the provisions of the Preamble to the Land Use Act which provides that: “”Whereas it is in the public interest that the rights of all Nigerians to the land of Nigeria be asserted and preserved by law. And whereas it is also in the public interest that the right of all Nigerians to use and enjoy land in Nigeria and the natural fruits thereof in sufficient quantity to enable them to provide for the sustenance of themselves and their families should be assured, protected and preserved.” According to the Court, per Ogunbiyi, JSC:

“Following from the foregoing re-statement, it is clear that the essence of the Act is to preserve and protect the rights of Nigerians to enjoy and use land, and further enjoy the fruits from the land. Citizens should be allowed to transact on their properties without unnecessary and undue interference by the State. By the phrase the enjoyment of the land and the fruits thereof should be given a simple and ordinary interpretation. In other words, the fruits of the land can be houses, installations in minerals and plants.”

Her Ladyship further stated:

“As rightly submitted on behalf of Respondent, the Act was enacted to address the problems of uncontrolled speculations in Urban Lands, make land easily accessible to every Nigerian irrespective of gender, unify tenure system in the country to ensure equity and justice in land allocation and distribution, and amongst others, to certain extent prevent fragmentation of Rural Lands arising from the application of the traditional principle of inheritance. The Consent Clause in the Act therefore gives the Governor the required supervisory control of lands in the territory.”

In Ibrahim v. Obaje, there was no conflict between the Respondent and the person from whom he purchased the subject property. The land was conveyed to him through an Irrevocable Power of Attorney over the property which was covered by a Certificate of Occupancy and Building Plan. The Appellant trespassed on the property, challenging the title of the Respondent. The Respondent sued the Appellant and succeeded. The Appellant’s appeal up to the Supreme Court was dismissed. The apex Court upheld the transaction giving proprietary rights to the Respondent over the property and refused to be persuaded by the Appellant’s contention that failure to obtain the consent of the Minister of the Federal Capital Territory before the transfer as claimed by the Respondent, renders the transaction a nullity.

In conclusion, it must be noted that the Supreme Court did not move to make the requirement of Governor’s consent unnecessary. The principle being established or rather, re-established, is that where the parties to a land transaction are at peace with their transaction, a third party (who has failed to prove superior title like the Appellant in Ibrahim v. Obaje) cannot rely on the absence of consent to nullify the transaction. In Ekpo’s case, there was conflict between the parties as to the validity of the purported transaction conferring or transferring title from the Respondent to the 1st Appellant. The Respondent was coerced by the Police into executing an instrument of transfer of his property to the 1st Appellant (his erstwhile employer) in exchange for freedom from detention and prosecution over an allegation of fraud by the Respondent. To that extent, absence of consent vitiated the transaction.

In Obaje’s case, there was no such conflict between the Respondent and the person through whom he claimed. The position of the Supreme Court is welcome. It is in line with the earlier observations of the apex Court in Awojugbagbe Light Ind. Ltd. v. Chinukwe where the provisions of Sections 22 and 26 of the Land Use Act were robustly considered. The case deactivated the apparent extremity of the effect of the strict interpretation handed down in Ekpo and other cases that followed.