Heritage Bank Ltd. v. Bentworth Finance Nig. Ltd. [2018] 9 NWLR (Pt. 1625) 420 at 435 paras G-H, per Eko, JSC:

“The point must be made as well that a seemingly endless chain of authorities have made it a settled principle of law that bankers who collect cheques and pay to those not entitled to the proceeds of the cheques are liable for the tort of conversion.”

Notes:

Eko, JSC above was actually citing with approval the holding of the Court of Appeal in the case, per Muhammad, JCA (as he then was). Interestingly, the Supreme Court had made similar remarks in the case of Trade Bank Plc v. Benilux (Nig.) Ltd. [2003] 9 NWLR (Pt. 825) 416 at 431, paras. A-B, per Mohammed, JSC. This case was not referred to. What was evident too was that both Heritage Bank Ltd. v. Bentworth Finance and Trade Bank Plc v. Benilux referred to the foreign cases of Kleinwort v. Comptoir National d’Escompte de Paris [1894] 2 Q.B. 157 and Fine Arts Society v. Union Bank of London (1886) 17 Q.D. 705. The Supreme Court in Trade Bank further referred to the foreign case of A. L. Underwood, Limited v. Bank of Liverpool and Martins (1924) 1 KB 775 from which the Court relied on the dictum of Bankes L. J. Notably, the case of Kleinwort v. Comptoir National d’Escompte de Paris was inadvertently stated as having been reported in 1984 in both Nigerian cases of Heritage Bank and Trade Bank instead of 1894.

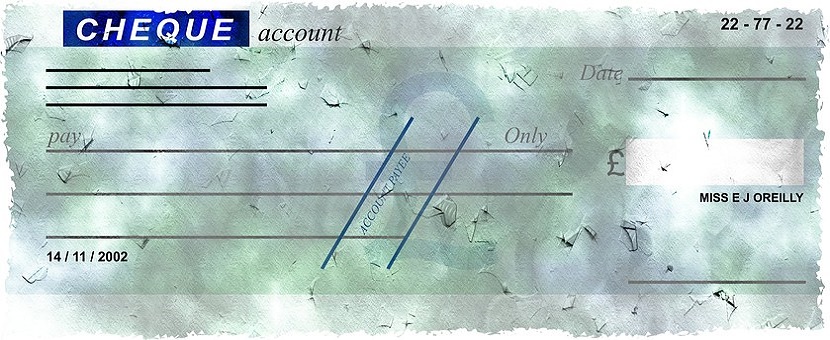

The facts of the case (Heritage Bank Ltd. v. Bentworth Finance) are that the Respondent bought a draft of N1 Million from Wema Bank, payable to a company, Teko Fishing Industries Ltd (TFIL). The payment was for services which TFIL rendered to the Respondent. The Managing Director of TFIL intercepted the bank draft and paid it into his personal account with the Appellant. Meanwhile, TFIL also had a current account with the Appellant. In spite of the fact that it was a crossed cheque payable only to TFIL with “Not Negotiable” boldly inscribed on it, the Appellant went ahead and gave value to the bank draft and paid the sum of N1 Million into the account of the Managing Director, instead of the payee of the cheque, TFIL. The Respondent’s case against the Appellant succeeded and the Appellant’s appeal up to the Supreme Court was dismissed.

At the Supreme Court, the Appellant contended that the Respondent must prove the actual loss it suffered by the Appellant’s negligent conduct. The Court discountenanced the argument. Eko, JSC reasoned that until the value of the bank draft was paid over, the draft could be counter-manded or re-purchased by the Respondent, the drawer. Beyond that, the Appellant was clearly liable for the tort of conversion as already established by decided cases and that the Respondent was entitled to recover the sum so converted. Significantly, it was immaterial that the person who received value for the bank draft was the Managing Director of TFIL, the actual payee of the draft. It is elementary principle that a company is a distinct personality and that accounts for the reason it owned a separate bank account in its name. The Appellant could not be excused on the basis that it reasonably believed the Managing Director would not misappropriate the funds belonging to TFIL. The relevant fact was that the draft was in the name of TFIL and was clearly marked “Not Negotiable” but the Appellant paid it into the personal account of another person not being the person entitled. Mohammed JSC aptly stated, while delivering his Judgment in Trade Bank v. Benilux (a similar case where the Appellant bank paid a cheque belonging to another to a stranger):

“The relief of the Plaintiff/Respondent is founded in the tort of conversion. This is clear, because the Appellant dealt with the Respondent’s cheque in a manner inconsistent with the Respondent’s rights whereby the respondent has been deprived of the use and possession of same. The tort of conversion is committed when the person entitled to the possession of a chattel is permanently deprived of that possession and the chattel is converted to the use of someone else.”

See Trade Bank Plc v. Benilux (Nig.) Ltd. (supra) at 430.